Large numbers of young people around the world – many of them underage – are compelled to marry against their will. There are many reasons this might happen: their parents may want to settle debts, make peace, or reduce the costs of marriage. Girls in particular can be forced to spend their lives with a husband who may be much older than they are. A range of such practices are found in Afghanistan.

In 1980, Afghanistan signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which calls for men and women to have the same right to enter into marriage and to freely choose a spouse. It ratified the Convention in 2003. Another two decades have passed, and despite consistent efforts by NGOs and other actors, forced marriages continue to occur. Cultural reasons are often given as an explanation, but a closer look reveals the complex nature of decision-making around forced marriage and the range of factors that contribute to it. Forced marriage is any marriage in which at least one of the parties has not themselves expressed their “full and free consent”.

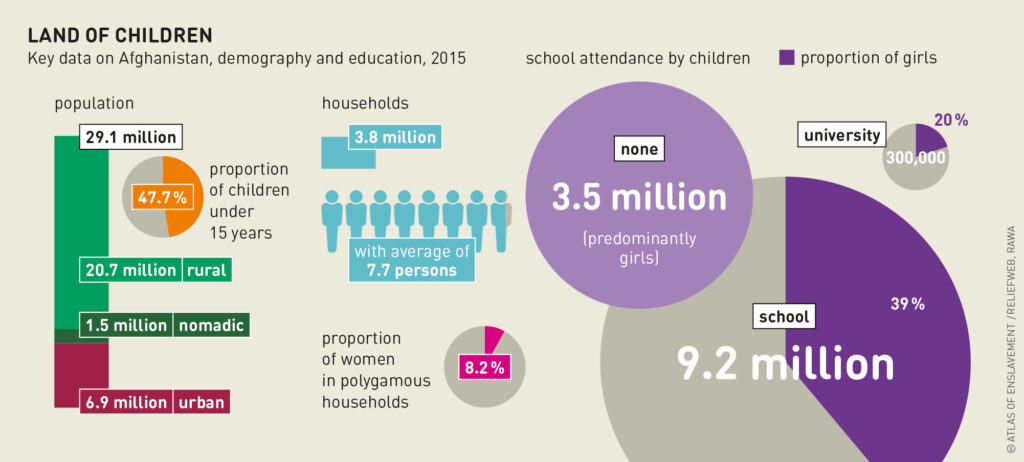

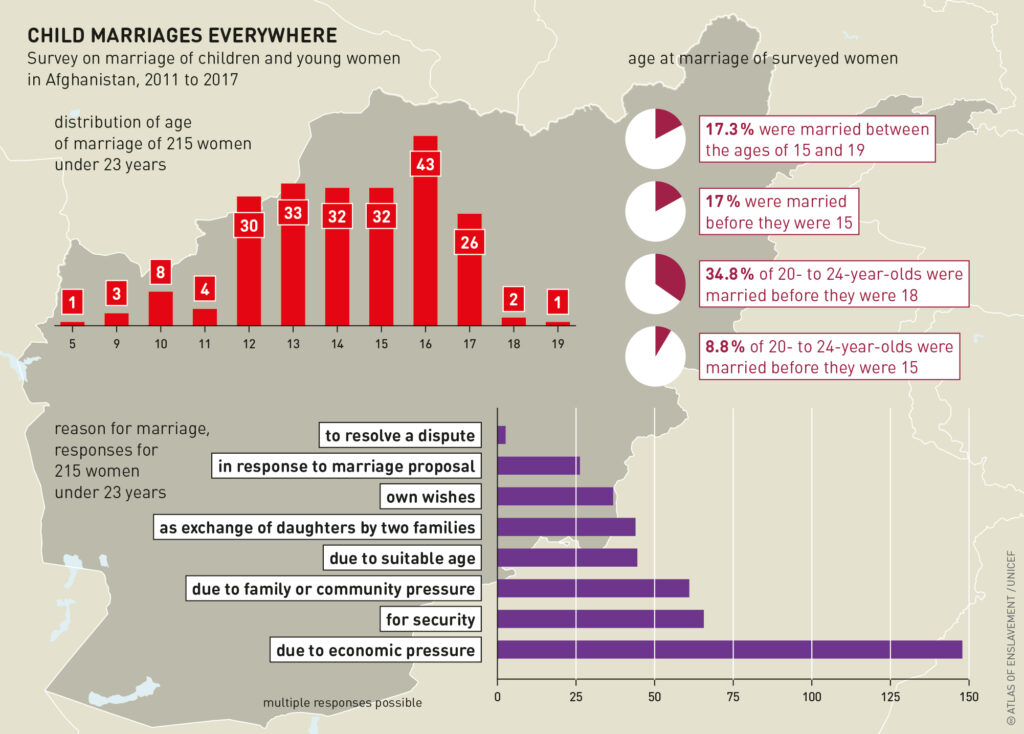

In Afghanistan, some estimate that the proportion of forced marriages may be as high as 60–80 percent. This includes those involving children, who, under international law, cannot consent to marriage. The 2016–17 Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey found that 28.3 percent of 20–24-year-olds were married before the age of 18, and 4.2 percent were married before the age of 15. Although the incidence of child marriage has been decreasing, but these reported rates remain high.

Several traditional practices contribute to the occurrence of forced marriage. Many cases of marriage for debt repayment, conflict resolution (baad) and bride exchange to reduce the costs associated with marriage (baadal) can be classified as coercion. Even if the participants are nominally willing, the financial or social implications may constitute an element of coercion. In a baad marriage, for example, a daughter is married into another family after a relative of hers commits a serious crime against that family – putting her in a situation where she can be held responsible for the crime and is at the mercy of her in-laws. More prosaically, an arranged match supported by the families and which does not fall under the above categories may also constitute a forced marriage.

Such marriages can be portrayed as the result of a patriarchal society, imposed by a single decision maker. Research in 2018 found that in the case of child marriage, almost 80 percent of respondents who had been married off before the age of 18 cited their father as the main person responsible. However, the same study found that male relatives were the loudest voices against child marriage, showing that they cannot be pigeonholed as consistent supporters of the practice. The process of decision-making around child marriage has been found to be more complex than unilateral, and may involve other family members and the child(ren) concerned themselves.

Reported drivers of forced marriage range from traditional social and cultural norms to security and financial reasons.

For child marriage specifically, economic pressure – both perceived and real – is the most common reason given by household members, followed by safety, and community pressure. Child marriage is broadly more common among rural and poorer households, but rates do not correlate directly to levels of income and debt, meaning that economics alone cannot explain its prevalence. Individual stories of forced marriage underline the role external pressure can play, with stories of abuse of power, threats of giving addresses to armed opposition groups, and even simply threats from (potential) in-laws.

The lack of a strong judicial system to respond to cases of forced marriage leaves many women without clear options for support, especially when their families have enthusiastically promoted the marriage. The legal age for marriage in Afghanistan for women is 16, which legitimizes certain child marriages. Zina laws to punish moral crimes have been used to prosecute some women who have fled forced marriages, in particular when tied to cases of sexual exploitation. At the same time, the laws that do exist against forced marriage are not fully implemented. Baad, for example, has been criminalized since the Afghan Penal Code of 1976.

The Law on Elimination of Violence Against Women of 2009 condemns child marriage and forced marriage, among other crimes against women, marking a significant positive legal evolution. But this controversial law, passed by presidential decree, has not been fully assimilated into the legal code nor practice. UN monitoring of crimes of violence against women and girls in 2018–20 found that only half of the cases reported made it to court. The system places a significant onus on the women concerned, meaning that most cases are likely to go unreported.

UNICEF and others have underlined the risk of child marriages increasing worldwide as the Covid-19 crisis worsens financial situations. The pandemic has exacerbated Afghanistan’s existing vulnerabilities, with immediate and long-term impact for girls. Furthermore, the Taliban took over the country’s government in August 2021. Given the history of forced marriage in Afghanistan, this raises real concerns around the phenomenon worsening again. Women and girls’ access to both employment and education has already been severely limited. Credible accounts report forced marriages to Taliban fighters already occurring across different parts of the country.