From ancient times, slavery has been an accepted part of life. That began to change only in the 18th century, when a few ethical thinkers realized that it was neither pre-ordained nor just. The human rights movement that they pioneered has caused societies around the world to shift from regarding slavery as normal to seeing it as an affront to universal freedoms.

Slavery can be traced back to many of the world’s oldest civilizations, from ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome to the Aztec and Mayan empires. But public efforts to end slavery in all its forms were far slower to develop. For millennia, societies tacitly or outrightly approved of slavery, and a number of philosophers, among them Aristotle and Plato, justified its existence by contending that “from the very hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule”. By the early 1700s, a new moral mindset was starting to take hold, particularly in the West, where many Christians were adopting an ideological shift from accepting slavery as a consequence of sin, to seeing it as an immoral and inhumane practice that needed to end.

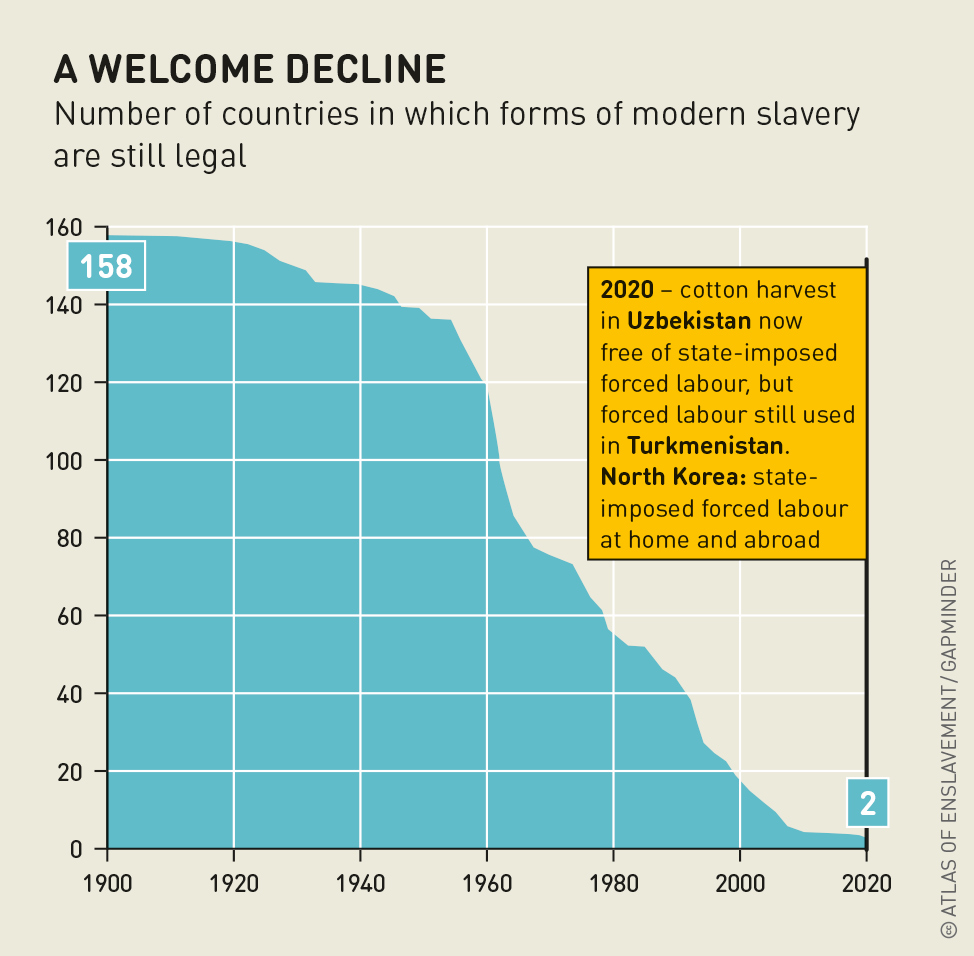

This would turn out to have a profound effect on the future of slavery around the world. In the United States and Great Britain, as testimonies of the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade began to surface, a number of Quakers mounted an opposition to slavery. This moralist movement, which began in the late 17th century in Pennsylvania, could be credited as the first real civil society action to end the institution. Largely defined as a community of citizens linked by common interests and collective activity, civil society is led by the people, not business or state actors, and its impact on politics can be significant. After 1783, when the Quakers issued the first anti-slavery petition to the British Parliament, the fate of millions of slaves around the world was slowly rewritten. By 1807, thanks to consistent lobbying and political pressure by the Quakers, Britain had abolished the slave trade within its colonies, a move which created a domino effect across Latin America, South Asia, Africa, and of course, the USA. The creation of the United Nations in 1945 and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 proclaimed, worldwide, the illegality and immorality of slavery – a notion that became widely accepted and formulated into national laws.

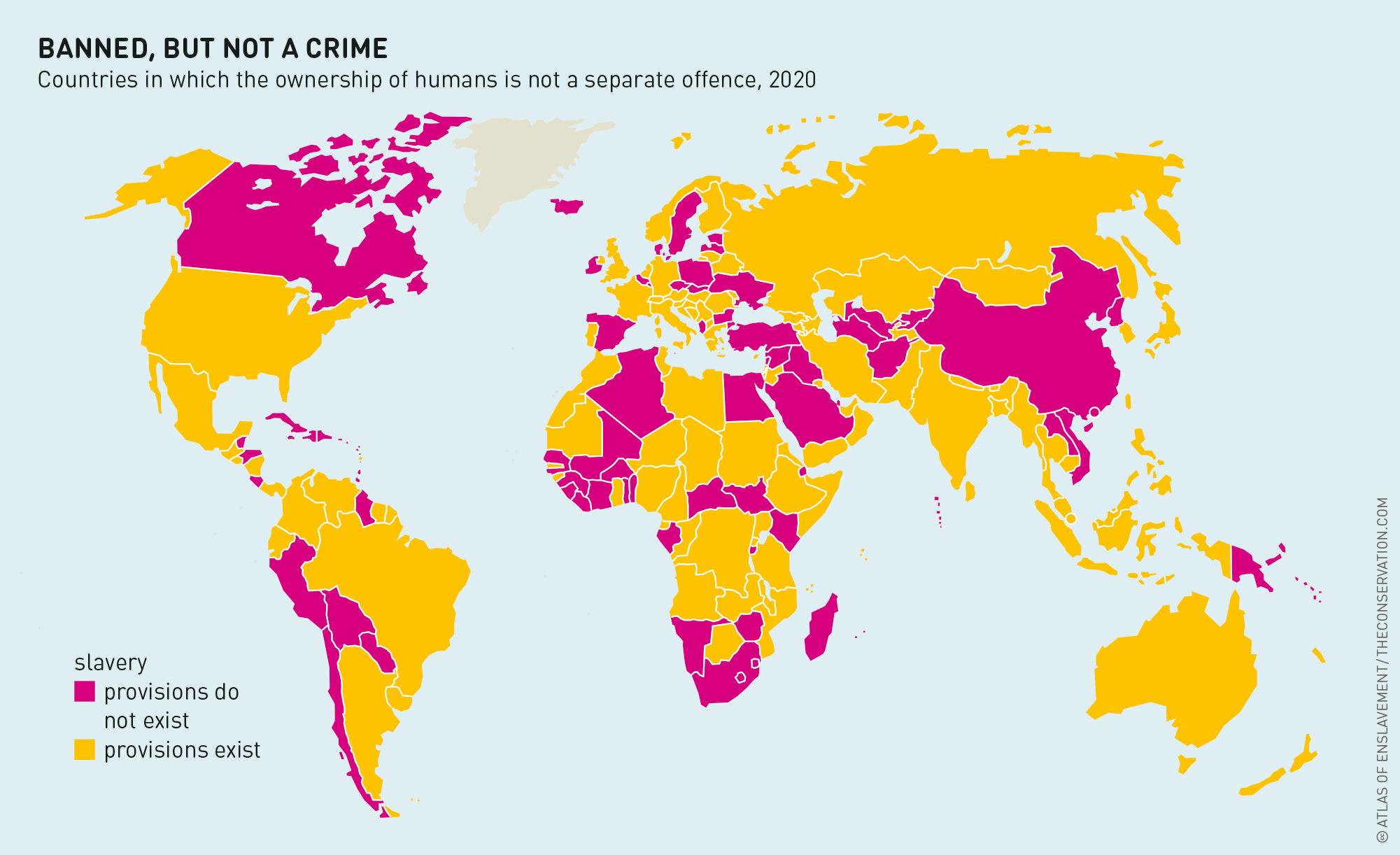

Why slavery still exists and why it affects so many people today are the driving questions behind civil society’s continued struggle to end it for good. At its core, slavery flourishes in places where the rule of law is weak and corruption goes unchecked, says Jasmine O‘Connor, chief executive of Anti-Slavery International, the world’s oldest human rights organization, which was founded by British Quakers in the 19th century to abolish the slave trade.

Today, the civil society actors fighting against slavery comprise more than just religion-based groups. Whether non-governmental organizations, labour unions, women’s rights collectives or survivors of slavery themselves, all play a pivotal role in holding governments and businesses to account, on both national and international levels. Civil society has been hugely instrumental in creating positive change, from boycotting goods produced through slavery to writing anti-slavery policies, and from lobbying governments to criminalize and eradicate slavery to providing services to help rehabilitate survivors. In Nepal, civil society has helped communities of agricultural bonded labourers gain access to redistributed land and subsistence grants. In Niger, the practice of women being forced into sexual slavery as a “fifth wife” was outlawed after NGOs supported a victim. In Mauritania, thanks to civil society assistance, two brothers who were born into slavery escaped from and then successfully sued their slave master, the first-ever prosecution of its kind in the African nation.

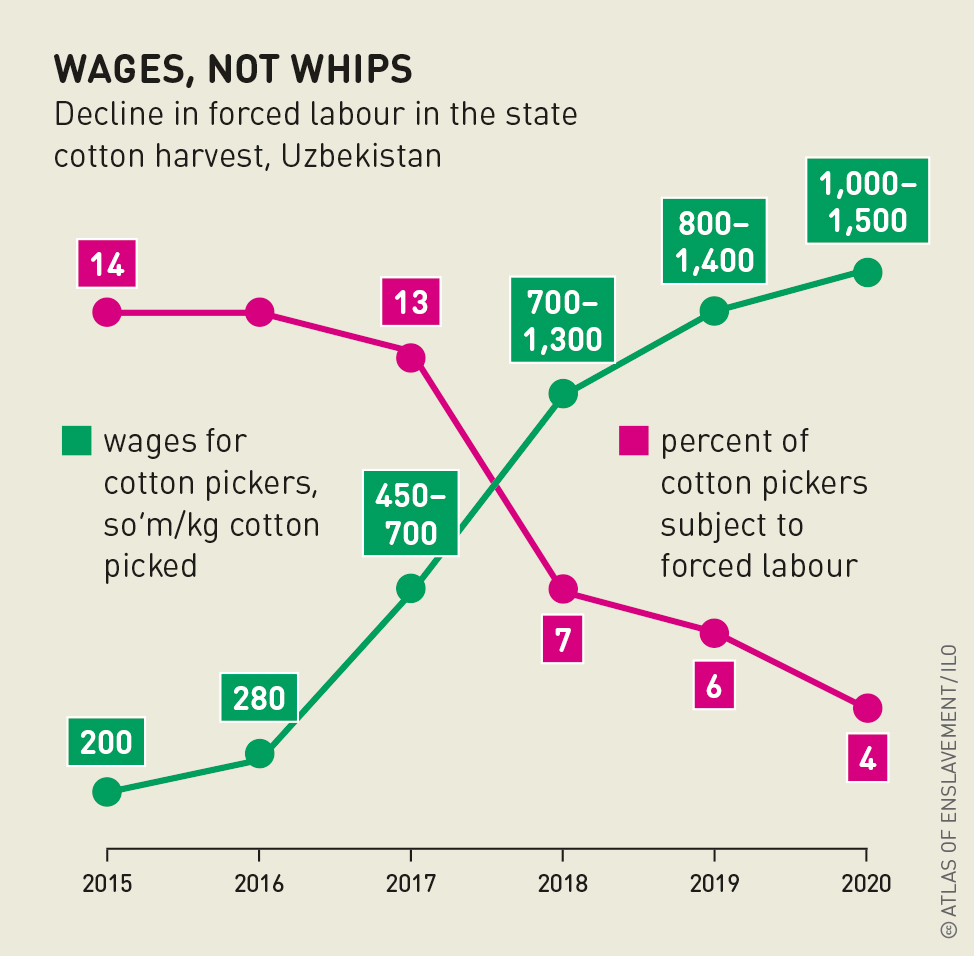

Just as was the case in ancient Rome, slavery today is big business; the difference now, O’Connor says, is that thanks to continuous lobbying by civil society, a growing number of start-ups are reimagining their business models to do “social good” rather than turn a profit at any cost. The most significant change has occurred within supply chains, where slavery can persist unchecked. Some governments, such as the UK, now require larger businesses to prove that they are taking steps to prevent slavery in their supply chains. Smaller companies in the fashion industry have been known to crowd-source funding in order to produce environmentally friendly, slavery-free clothes. Ultimately, O’Connor says, civil society’s role is to know when to effectively challenge governments and businesses to do more to fight against slavery, and when to collaborate to help them be as effective as possible.

Achieving that balance is not always easy. Partnerships among civil society groups are often lacking, with insufficient funding, inadequate resources and poor coordination diluting their overall effectiveness, says slavery expert Siddharth Kara of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. As civil society actors compete with each other for a shallow pool of donor resources, they fail to provide adequate survivor protection or empowerment, affecting the leadership of the anti-slavery movement as a whole, says Kara. He concludes that governments, charitable foundations and businesses must invest more in the anti-slavery movement, as well as fund research on where the money is needed most, if the practice is to ever be eradicated for good.