Slavery can take many forms – some severe, others less so. There is little consensus on what constitutes slavery, and the boundaries between slavery and other forms of exploitation and injustice are blurred. Slavery must be seen in the context in which it arises, for only then will the fight against it be effective.

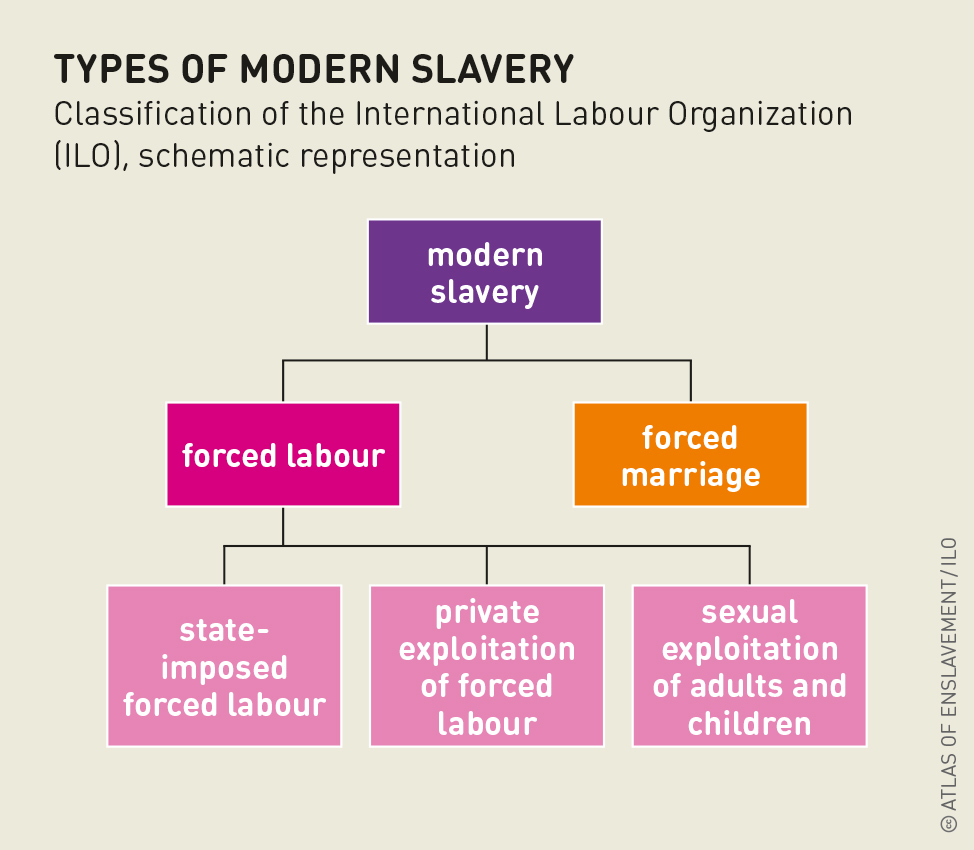

What is modern slavery? There are highly differing viewpoints on this. They all have certain criteria in common: a lack of consent, the use or threat of force, and an element of exploitation. A lack of realistic alternatives due to structural violence and poverty can also lead people into slavery with their eyes open. Modern slavery occurs when working conditions are classified as illegal or if they exceed a threshold of acceptability. Institutions such as the International Labour Organization and non-governmental organizations such as Anti-Slavery International, Walk Free Foundation und Free The Slaves emphasize slightly different aspects.

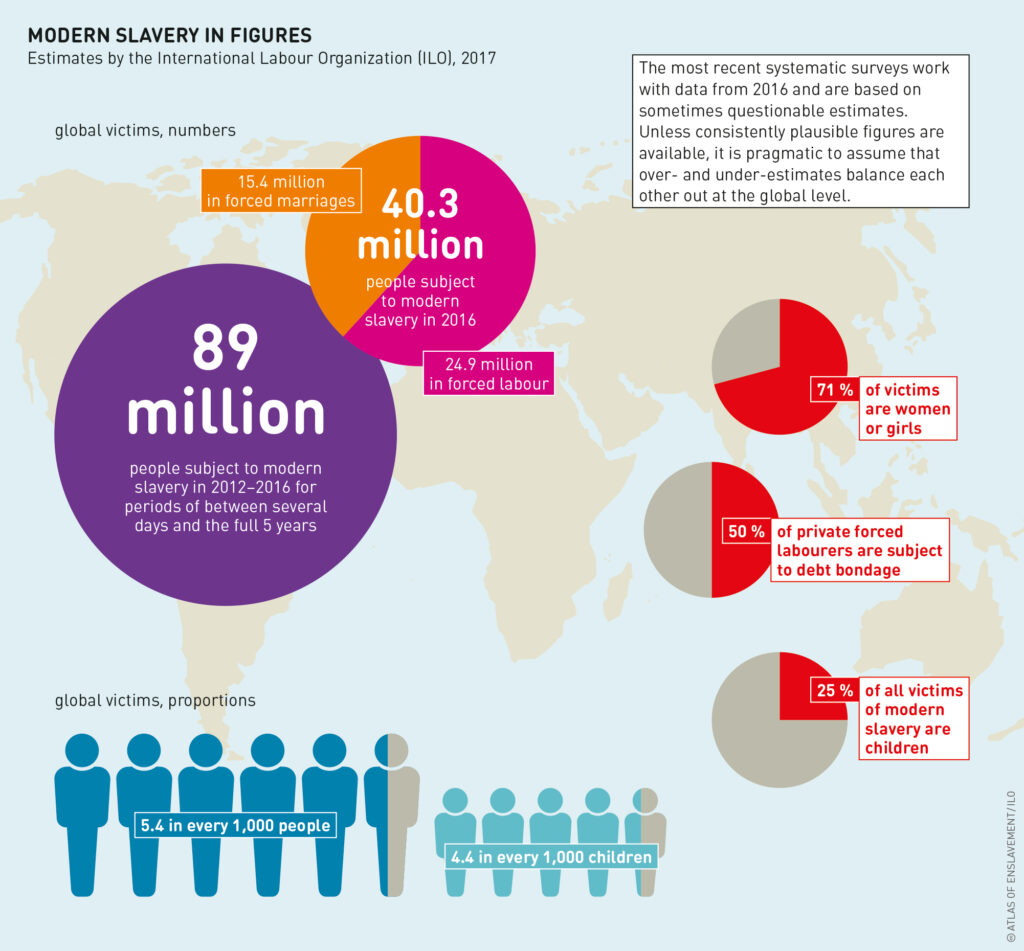

Debt bondage and contract slavery constrain victims through debt via loans and so-called advances, and partly also through force and the confiscation of passports. Work contracts may be seasonal; the debts may be impossible to repay, and may be inheritable.

Migrant women are often forced to do domestic work in private homes. They may be disenfranchised, and subjected to violence and working conditions from which it is extremely difficult to escape. Such arrangements occur in almost all countries worldwide.

In chattel slavery and origin-based slavery, individuals are born, kidnapped or sold into slavery. Many belong to ethnic groups, classes or castes at the bottom of the social hierarchy. They are employed mainly in domestic work, farming or herding.

In ritual slavery, girls are given to priests to work in their houses or fields, and to serve them sexually, until they become pregnant or get older, when they are replaced by other girls. This practice is banned under the law but may be recognized under local, religious or customary rules in West Africa and India.

Forced labour refers to work that is performed against the will of the person concerned under the use or threat of violence. It is practised by individuals, states, military groups or companies, particularly in domestic, agricultural, construction, factory and sex work.

Human trafficking, on the other hand, involves moving people for the purpose of exploitation to another location against their will, under the threat or use of violence or with false promises. The boundary with (voluntary) people-smuggling can be blurred if part of the migration process takes place under duress or if a migration that started voluntarily ends up in a forced labour relationship.

Child labour exists worldwide too, in children’s own families and elsewhere, in companies, domestic work, through forced marriage, and in numerous branches of industry and agriculture. The classification of child labour as slavery is controversial, especially in relation to the difference between labour that is self-determined and determined by others, between legal and illegal forms, and in terms of the definition of childhood. Under international law, someone under the age of 18 is classified as a child, but both this age limit and the claim to a protected childhood is criticized by some as a Western concept. Depending on the perspective, forced marriages, genital mutilation and organ trafficking are also described as modern slavery.

Critical voices doubt that a core definition with fixed criteria will help rid the world of modern slavery and slavery-like conditions. The forms of slavery are just too varied. Instead of a definition, one proposed approach is a spectrum that places modern slavery somewhere between chattel slavery, as the most extreme form of bondage, and freedom. Critical slavery studies reject the concept of modern slavery altogether as it ignores other forms of exploitation, coercion and bondage, or indirectly even legitimizes the latter by distinguishing them from illegitimate modern slavery.

The approach that governments use to deal with modern slavery also raises doubts. The measures they take to combat slavery or sex work can further weaken and marginalize those affected and push them further into the realm of illegality. However, the demand to waive any definition of slavery would not change the conditions which enable slavery – and it would hamper judicial mechanisms against the practice.

At the same time, plain definitions do bear the risk of separating modern slavery from its political, economic and social context – especially where the focus is on individuals only, either victims or perpetrators. It is therefore important to consider the situation not only during enslavement, but beforehand and afterwards, as only long-term measures embedded with encompassing human rights politics can avoid the risk of people becoming enslaved, maybe even again.

Taken together, these views give a varied picture of modern slavery that cannot be reduced to a single definition. It is crucial to view modern slavery, bondage and exploitation in the contexts within which they occur. Doing so reveals the social, political, cultural and economic inequalities, especially in terms of gender, class, caste, ethnicity, family status, age or nationality, that are preconditions for enslaving people.