In the mind of most Europeans, slavery is something that happened long ago and far away. But it still exists today in Europe, hidden from view. Not millions, but still tens of thousands of people work in forced prostitution, debt bondage and livestock raising.

The vast majority of forced prostitutes in Europe come from eastern and southeastern Europe. One country – Moldova – has stood out in the last 25 years. The involuntary prostitutes are almost all young women, including some underage girls. Many come from rural areas of Moldova, often from poor, neglected backgrounds or dysfunctional families, and most have spent only a few years at school. They are lured abroad with promises of a well-paid job as a babysitter, waitress or care worker. The destination countries include Germany, Italy, Spain and Turkey. Once they arrive, they are forced into prostitution and are kept under permanent surveillance. Their identity cards are taken away to prevent them from fleeing.

Around the year 2000, thousands of cases of forced prostitution were reported in Moldova. Public awareness campaigns and hefty punishments for traffickers and pimps have cut the numbers significantly in recent years. But in 2019, the police still recorded 52 cases of forced prostitution; in 2020 the figure was 24. The number of unreported cases could be much higher, say officials.

In the Czech Republic, it is not poverty but rising prosperity that is leading to the spread of slavery-like living and working conditions. A severe labour shortage has arisen in the low-wage sector. Workers from poorer EU member states such as Romania and Bulgaria, who otherwise might fill these positions, are drawn instead to the higher wages offered in wealthier western European countries. The Czech government therefore supports the recruitment of temporary workers from non-EU countries such as Ukraine, Mongolia and Vietnam. In the past 10 years, around 20,000 Vietnamese workers have officially come to the Czech Republic.

In Vietnam, work visas and temporary employment contracts are practically available only via local agents who are often members of criminal networks. The job seekers each pay them between 10,000 and 20,000 US dollars for arranging work and a visa. Their contracts in Czech firms are generally valid for one or two years. Because the workers usually only receive minimum wage, minus the costs of board and lodging, they cannot repay their loans on time. After the end of their contracts, many stay on in the Czech Republic illegally.

Without alternatives, many work under slavery-like conditions to produce drugs. The Czech Republic has long been one of the biggest producers of the illegal synthetic drug methamphetamine, or crystal meth, a business largely controlled by Vietnamese criminal organizations. The indebted migrant workers work in illegal meth labs or indoor cannabis plantations. Some are trafficked to other countries in Europe, including Germany, where Berlin is a major centre of organized Vietnamese criminality. The victims almost never try to resist their tormentors due to the threat of reprisals against their families back home, or the theft of their property. In addition, Vietnamese migrant workers face great social pressure from their home country to find success overseas.

A brutal form of modern slavery exists in several countries in southeastern Europe, particularly Romania. In remote pastures, thousands of livestock are tended by shepherds who live in tiny huts, with minimal food and often without pay. Except for a few hours’ sleep, they must work round the clock, herding and milking sheep and goats, producing cheese, and mucking out enclosures.

Sheep keeping in Europe has experienced an exceptional boom in the last decade, stimulated by the strong demand for live animals and meat from the Middle East. Romania has around 12 million sheep and goats; among EU member states, only Spain has more. The work of shepherds is unattractive because it is extremely difficult and poorly paid, so many livestock owners recruit workers from among the poorest villagers, including minors and even children. In previous years, a series of cases were documented where adults and children were mistreated, chained at night, and half-starved. Despite this, the authorities still rarely check the working conditions in livestock farms.

Europe, and especially the European Union, has better laws against modern slavery than any other continent. The fight against slavery is part of today’s European values. But economic interests and a lack of political will still lead to states tolerating slavery-like exploitation, and to authorities not adequately controlling working conditions. Europe is still a long way from solving the problem of modern slavery.

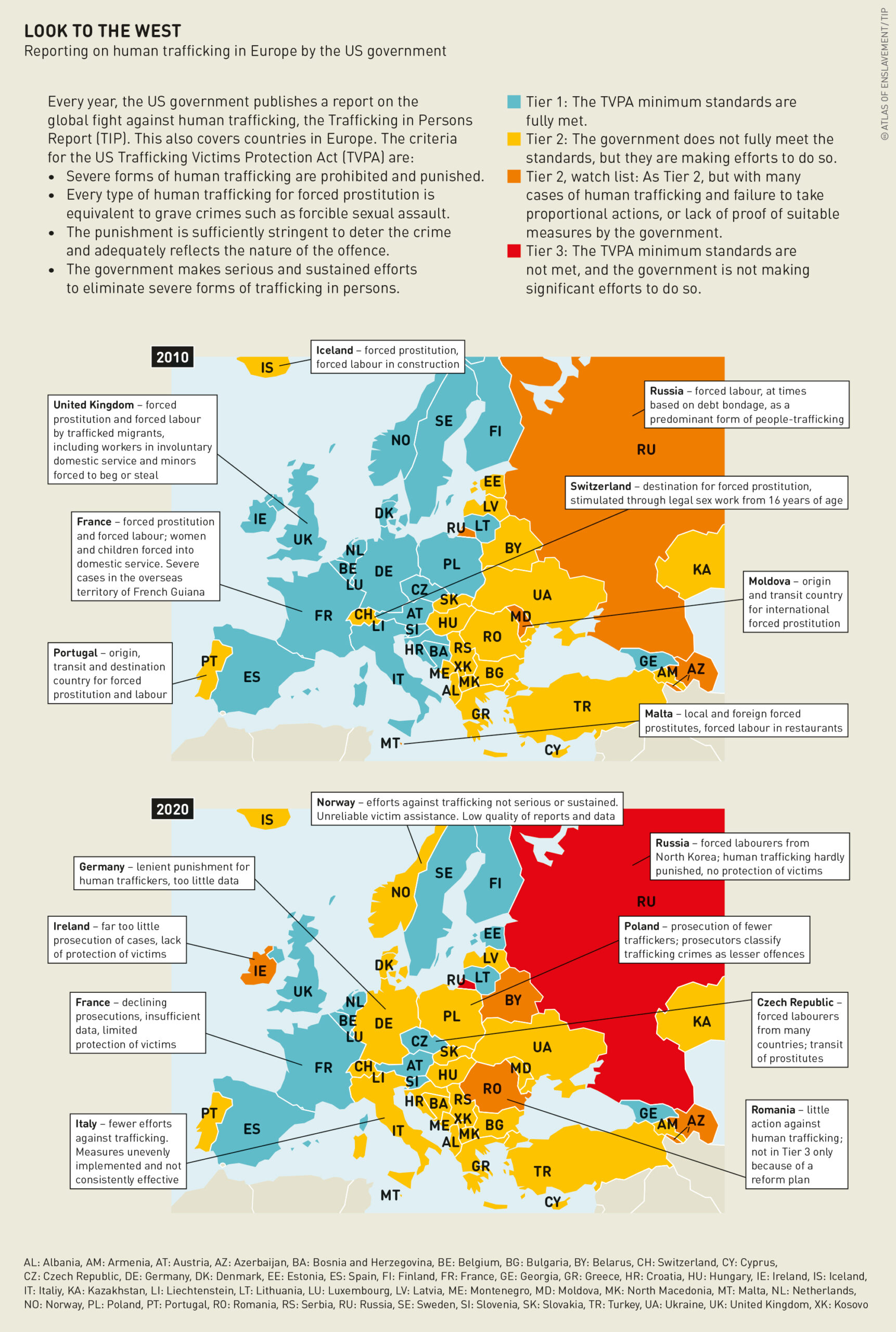

pages of analysis for countries around the world. But some

experts question the validity of the classification into tiers