Haiti is rightly proud of the fact that it is the only nation to be founded after a successful slave rebellion. But slavery of another type is still prevalent throughout the country. Poverty makes rural families send their children to work in urban households.

The Caribbean nation of Haiti was founded in 1804 when it declared independence after overthrowing slavery through a rebellion led by the enslaved. Despite the legacy of this victory and the central place of freedom and humanity in Haitian culture, there now exists a widespread system of child domestic slavery, known as restavèk. This practice can be traced as far back as the early 1900s. In it, children as young as five are made to perform arduous and dangerous household tasks in the homes of strangers or extended family members. While placing children in people’s homes is not unique to Haiti, what defines the restavèk system is the exploitative nature of the work and the violence and abuse associated with it.

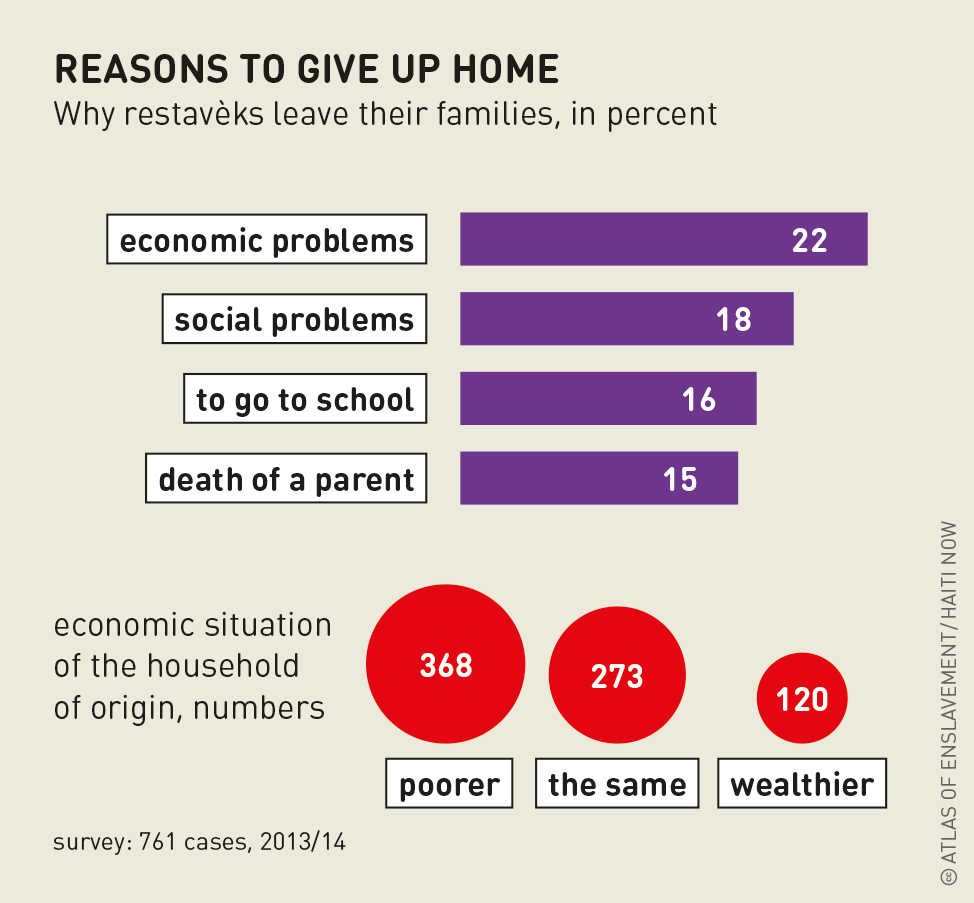

Extreme poverty is at the root of the system. Most restavèk children come from families in rural areas where people have little or no access to employment, education and health care. Mountain communities are isolated and lack infrastructure. Many parents choose to send their children to urban areas where they can stay with a family and perform household work in exchange for food and, in some cases, schooling. Many parents are not aware of the severity of the situation they are sending their children into – and those who understand the risks weigh them against their children’s chances if they stay home, where food is scarce and education unattainable.

Although not all children in such arrangements experience abusive and violent treatment, the Creole word restavèk (translated as “lives with”) is used as a derogatory term for those in situations comparable to child slavery. Approximately two-thirds of children in the restavèk system are girls, and this is reflected in the gendered labour they perform, with tasks including fetching water, cooking, cleaning, shopping, and looking after other children in the household. For the most part, restavèk children themselves do not get to attend school as this would interfere with their work. Most schools in Haiti also charge fees, so this would be an added expense for the household.

The households that take in restavèk children may only be in marginally better financial positions than the rural homes the children come from. It is poverty that creates the household’s need for an unpaid worker. The tasks a restavèk child performs tend to be those for which women are typically responsible. But women in poor, urban households often need to spend most of the day outside the home in order to earn money – in markets or factories, or as street vendors.

A restavèk child is taken in to assume these women’s household responsibilities, which often include arduous and dangerous work such as carrying heavy loads or cooking on open fires.

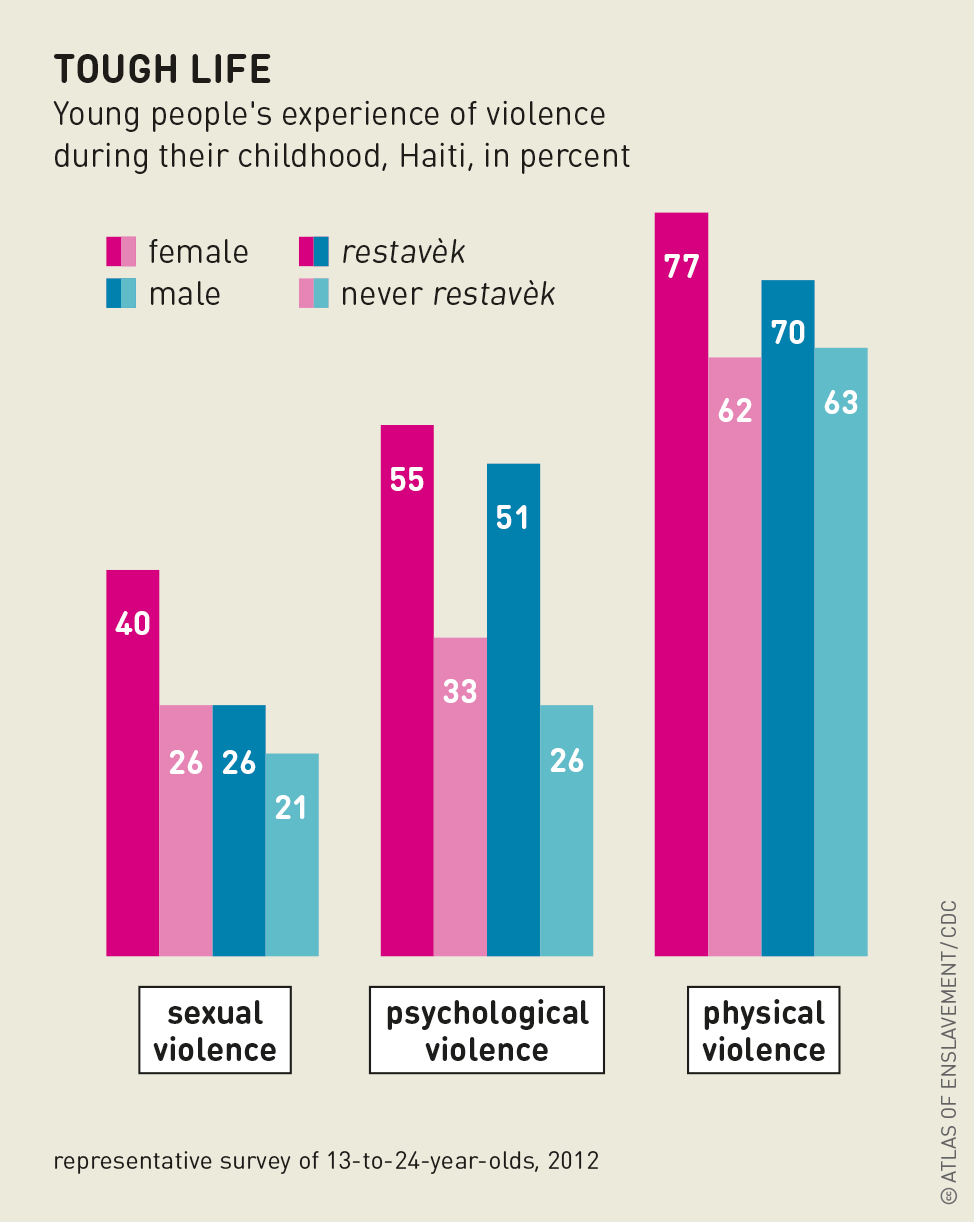

The element of violence in the restavèk system is one of its defining features. The children are typically exposed to physical, sexual and emotional abuse. As well as being subjected to long working days and heavy workloads, restavèk children tend to be treated with contempt by the members of the household they serve. Excluded from meals, dressed in frayed clothing, and with no care given to their hair or physical appearance, they survive on the household’s discarded items and leftovers.

Restavèk children also serve as outlets for anger and frustration. They may have to endure physical beatings and punishments with whips, boiling oil or a hot iron. Their vulnerability and lack of value in much of society’s eyes expose them to sexual abuse, including rape, which may lead to pregnancies and enforced and risky abortion attempts.

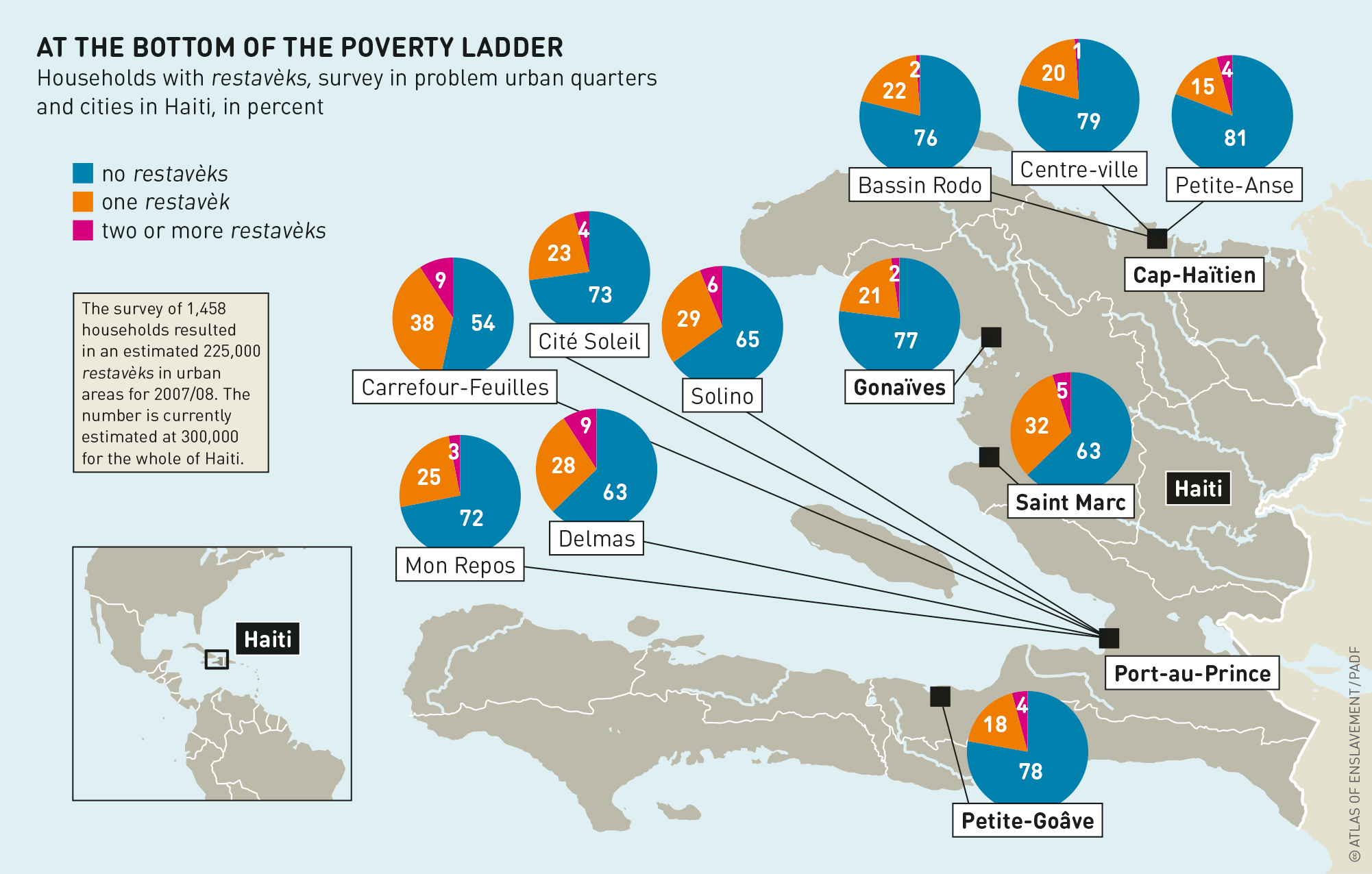

The number of restavèk children in Haiti is unknown, but estimates are upwards of 300,000. The introduction in 2014 of an anti-trafficking law and a national action plan has seen an increase in the state’s efforts to address the issue. While some convictions have been made, the numbers remain extremely low, and the government has been criticized for doing too little. Moreover, the state lacks the resources to tackle this issue, which is just one of many social and economic challenges facing Haiti. Most of the interventions that do exist focus on removing children from the worst situations. However, family reunification is not always possible, nor does it address the factors which led to the trafficking in the first instance.

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, and women are especially affected. The intersection of poverty and gender is central to the restavèk practice. In a worsening political and economic climate, addressing the root causes of this practice seems almost impossible. While efforts continue to scale up the application of the anti-trafficking law, children will still be vulnerable to the restavèk system as long as poverty, gender discrimination and access to education remain major issues.