Europe prides itself on its model of social justice, its welfare state, and its ability to ensure that its citizens can lead a decent life. But below the surface, hundreds of thousands of people – many of them migrants – are being exploited.

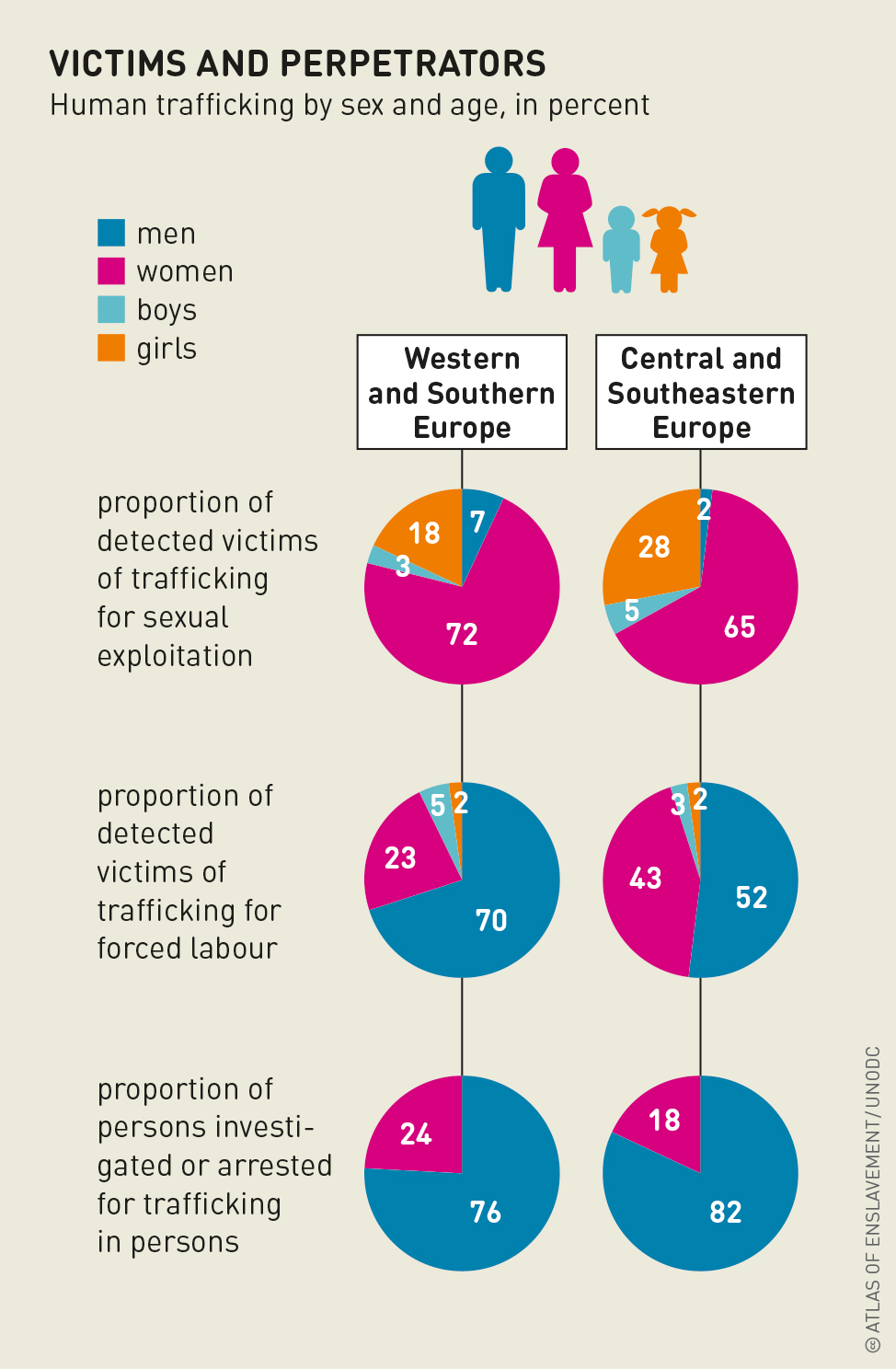

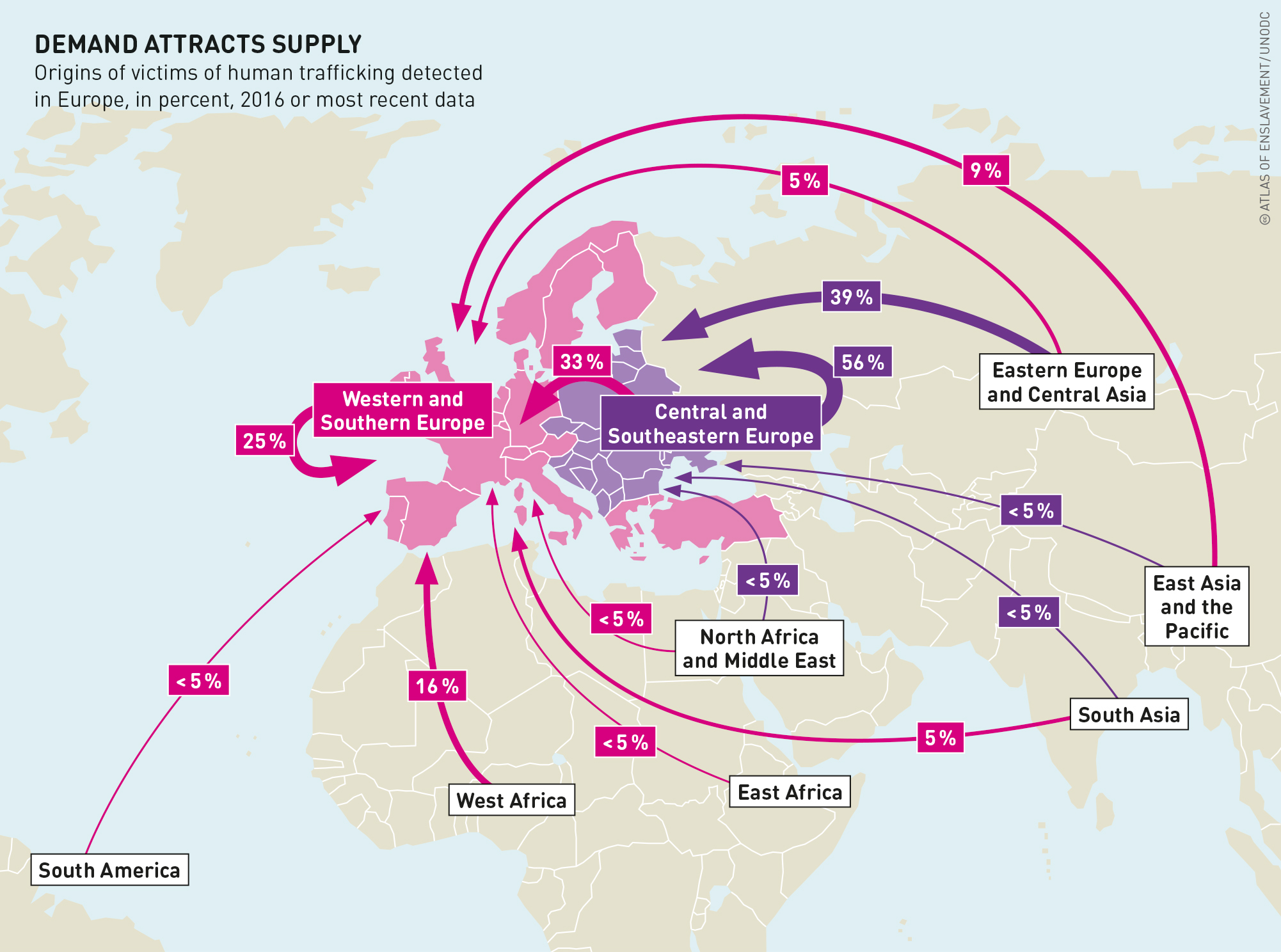

Forced labour in Europe? Many people hardly believe that it exists. But the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated that in 2012, 880,000 people in the continent were exploited under some form of coercion. Some 270,000, or 30 percent, were victims of forced prostitution, while the other 70 percent, or 610,000, were forced into other kinds of labour. Since then, the number of unreported cases has risen further. Contrary to these estimates, the official figures – the number of cases of forced exploitation and forced labour recorded by the authorities – are vanishingly small. In 2018, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) identified only 5,500 victims of human trafficking in southern and western Europe, of whom 66 percent were subject to sexual exploitation and 27 percent to forced labour. A breakdown of the ILO figures shows 100,000 victims of forced labour in Germany alone. But a situation report by Germany’s Federal Criminal Police Office in 2019 listed just 287 criminal cases on sexual exploitation and only 14 on forced labour.

The public awareness of forced labour is generally much lower than that of forced prostitution – which also gets much more attention from law enforcement agencies. Both male and female victims of forced labour are not generally regarded as victims, nor do they necessarily see themselves as such. The experiences of counselling centres and trade unions repeatedly confirm how vulnerable migrant workers in Europe are. People who flee poverty and a lack of prospects in order to seek a better life elsewhere often do not know their rights, are not organized into unions, and lack social support and networks.

People in Europe who are exploited often live isolated lives. Their residence status may be unclear; they may work extremely long hours for low wages. Their employers often control them closely, for example by restricting their social contacts. They may live in locations far from other people, or directly adjacent to their place of work. They may lack language ability and not know where or how to get help and support. Their dependence on their employers is indirectly perpetuated by poverty and a lack of documents or work permits. Migrant workers may be put under pressure by being forced to repay their travel costs or other debts, by threats of deportation or even force – directed towards them personally or towards their family members.

Exploitation may occur in almost any economic sector. The potential profits for the employers are enormous. In 2014, ILO estimated that the annual profits from forced labour in the European Union and other developed countries in the Global North amounted to at least 47 billion US dollars. Globally, they exceeded 150 billion dollars. In 2016 in Italy alone, the Italian research institute Eurispes put the profits from the forced exploitation of migrant agricultural workers by mafia-like organizations at 21 billion euros. According to the trade union FLAI-CGIL, over 430,000 people are involved in mafia structures in Italian agriculture. That figure includes 100,000 people living in degrading conditions in illegal slums, far from any town, without sewerage, water or infrastructure. Around Caserta, north of Naples, women from eastern Europe pick strawberries. Africans are hired to harvest oranges. Apples, grapes, melons, tomatoes and countless other fruits and vegetables are gathered under such conditions. The work may last 14 hours a day, from four in the morning until six in the evening. Every year, some workers collapse in the fields and die.

For migrants, the risks of exploitation are high in low-wage jobs such as in the meat industry, catering, construction, care, or seasonal agriculture. This is especially true for workers who lack documents and residence permits. A similar situation occurs in sectors that are organized through subcontractors, such as logistics and cleaning services. For the perpetrators, the risk of punishment is generally close to zero.

Workers in exploitative jobs who are discovered by the police or customs authorities are generally not informed of their rights, nor are they seen or treated as potential victims. In the best case, they are deported without being given the opportunity to claim any wages they are owed. In the worst case, they incur criminal charges for working without a labour or residence permit. This means that most victims of forced labour and labour exploitation do not appear in the official statistics. This in turn leads to a lack of understanding on the part of law enforcement agencies when counselling centres and trade unions call for a more consistent implementation of victims’ rights and protection against and prevention of forced labour.

The extent of labour exploitation and forced labour must be recognized by society as a whole, in politics and in the statistics for all European countries. Injustices must be prosecuted through the law. People continue to be ruthlessly exploited in many economic sectors and industries, without any consequences for the perpetrators, and without the victims being able to claim their rights. Some countries have taken small steps against labour exploitation in individual sectors, such as the Labour Protection Control Act in the meat industry in Germany. That is a start, but it is not enough.