Most countries around the world have banned slavery and forced labour. North Korea, however, actively engages in these practices, both at home and by sending workers abroad to work long hours for next to no wages. The government in Pyongyang pockets the profits and ruthlessly punishes anyone who protests.

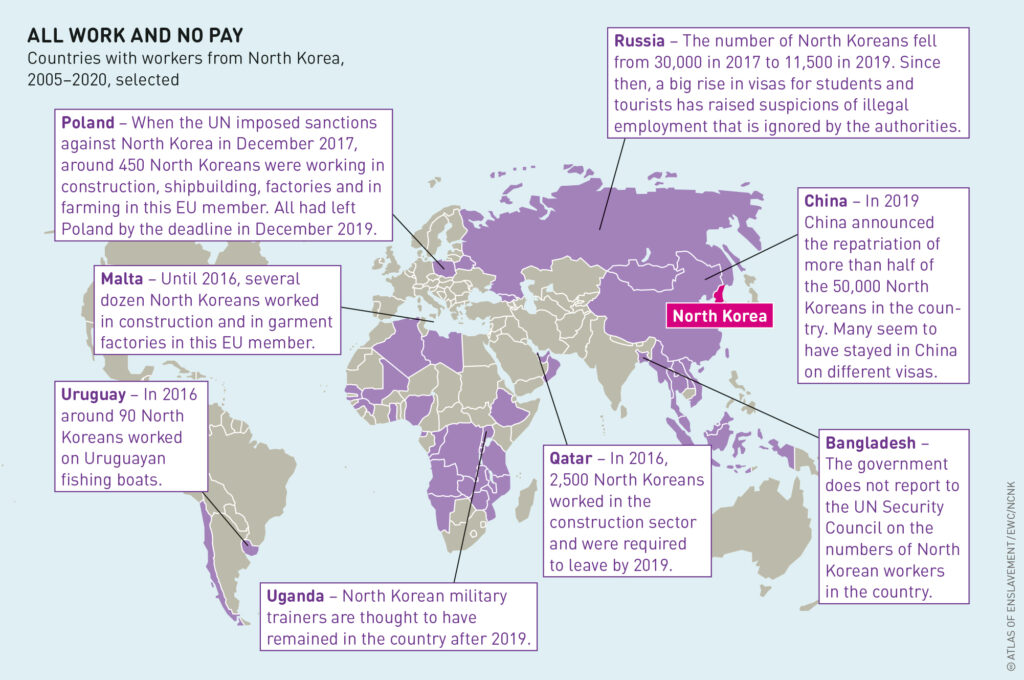

The number of North Koreans who work abroad has risen greatly over the last few decades: estimates range from 50,000 to 150,000–200,000. The UN sanctions that took effect in December 2019 formally ended this, although it is clear that the countries to which most North Korean workers are sent – China, Russia and the Gulf states – have not been enforcing these sanctions, or enforce them only partially, and continue to work with North Korea as a partner.

It is no coincidence that North Korean workers often end up in the countries that traditionally have close ties with the government in Pyongyang. North Korean workers have worked, or still work, in more than 40 countries, especially China, Russia, a number of African and Middle Eastern states, the EU, and Mongolia.

A crucial element of North Korean labour abroad is that it is state-controlled from beginning (selection, training, deployment) to end (employment, payment, repatriation). The work practices strongly resemble human trafficking. Even when selected workers have gone abroad voluntarily, they have been fraudulently informed about what is expected of them, how much they will earn, or what rights they have in the host country.

Once they arrive, they cannot say no to work or to any other demands made on them. Disobedience – or worse, attempting to leave – leads to punishment on the spot and later at home, where their families also face danger. Passports are immediately taken by the managers on arrival and kept in the North Korean embassy or a similar place. In the EU, workers receive neither an individual employment contract nor an individual bank account, although both are required by law.

Depending on the place of deployment, regional differences can be seen in the treatment and working conditions of North Korean workers. But the same structure underlies all work assignments – whether in Malta, Berlin, Dandong or Dakar – and there are recurring elements. The main reason for hiring North Korean workers is that they work for prices far below the market level. In Poland, shipbuilding companies deliberately exploit this by employing North Korean welders.

Moreover, the agreed wage is never what the workers themselves receive. Up to 90 percent of wages are withheld – or even 100 percent, as in Kuwait, where in 2016 this caused so much unrest among the workers that they were hastily taken back to North Korea. The percentage withheld varies from place to place. Some of the money is sent directly to the North Korean state, and some is pocketed – without state sanction – by managers on the ground. Interviews with former workers show how dire their financial situation was. They often could not

save any money at all to go home, and their livelihoods were precarious.

Another reason employers find expatriate North Korean workers attractive is that they routinely work extremely long hours. This seems to be the case everywhere. A working day of 12 hours is normal and often extends to 15–16 hours. There are cases of people working around the clock to meet deadlines. Overtime is often not paid separately to workers.

The low costs associated with hiring workers from North Korea extend to their tools, working conditions and protective clothing. Both in Russia (during the construction of the Zenith Stadium in St Petersburg, for example) and in the shipyards in Poland, workers have worked without safety shoes and hard hats. It has become common knowledge among North Koreans back home that working abroad can mean returning in a coffin. This changed somewhat after 2014, after a UN Commission of Inquiry issued a report on human rights violations in North Korea. But even after this, many North Korean workers, such as those in Polish shipyards, continued to lack the necessary safety equipment, which led to one employee burning to death.

The structure of global posting and hiring of North Korean workers uses a system of subcontracting, whereby joint ventures between representatives of the Pyongyang government and local businessmen aim at maximum returns in terms of labour from an absolute minimum investment in wages, accommodation and food. The lowest possible wages, the squeezing of additional costs and maximum exploitation of the workers through unpaid overtime are crucial elements of this structure. The North Korean state and the local employer share a common interest in paying the workers as little as possible.

This structure has local variations around the world, but these core elements are present everywhere. Without them, North Korean workers would lose their appeal abroad. In most cases it is not their expertise (with the exception of, for example, building large bronze monuments), but the fact that they are much cheaper than other workers and are unable to say no, that makes them desirable.

The role of the state is worth noting. Although the management of labour abroad is supervised by various North Korean enterprises, departments and military units, the imperative to send labour abroad comes from the government. So do the administrative preparations, maintaining contacts with host countries, selecting the workers, setting the parameters, and receiving the money they have earned.