Modern slavery is not defined in international law. But in recent years it has gained popularity as an umbrella term for legally defined concepts such as forced labour, human trafficking, slavery, slavery-like institutions and practices, and servitude.

There is no internationally agreed definition of modern slavery that is central to existing legal instruments. So to understand the international policy framework around the issue, it is necessary to look at how exactly lawmakers seek to address forms of coercion and severe exploitation.

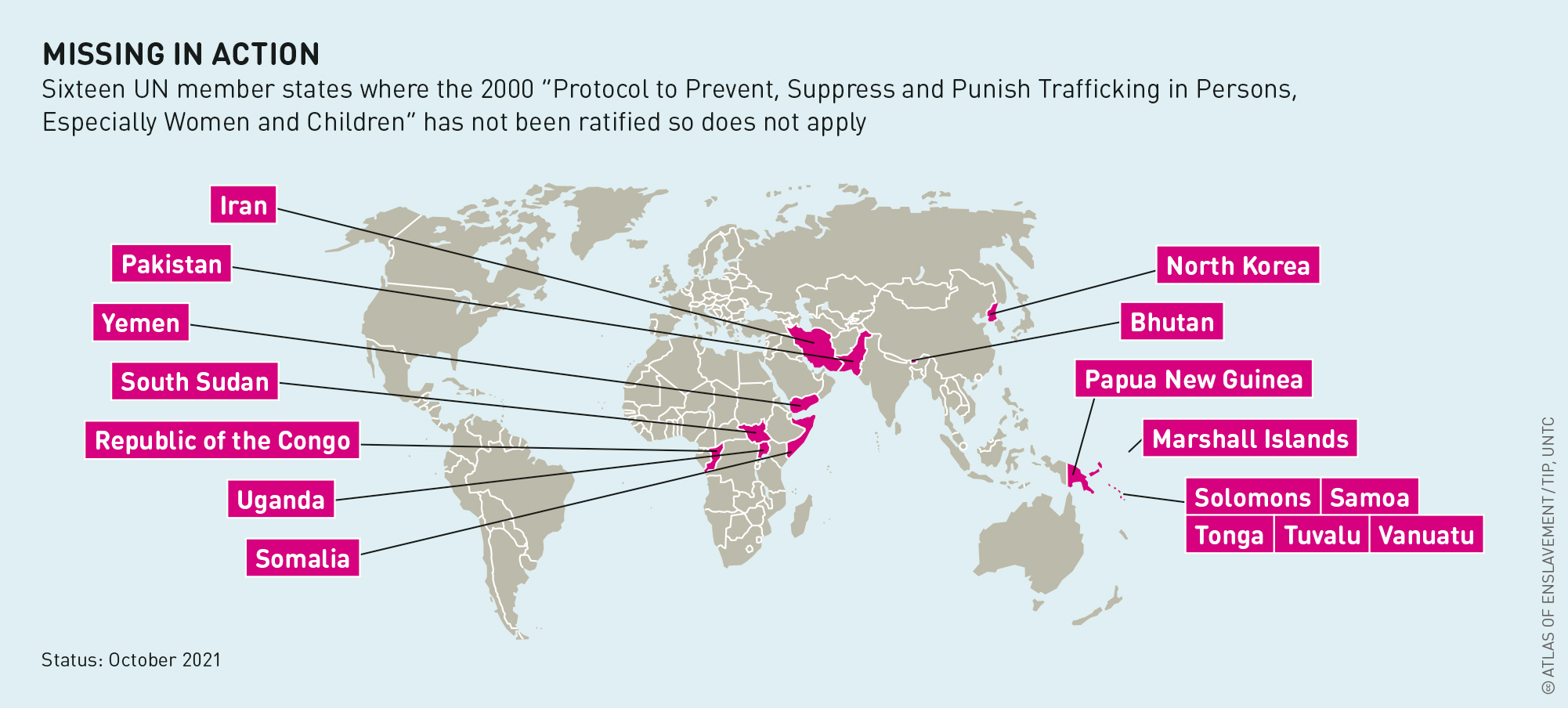

Despite the lack of a legal definition, many efforts have been made over the last two decades to address the problem of modern slavery. One international instrument that has resulted in a large amount of national and regional legislation is the Trafficking Protocol to the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, or UNTOC, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2000. This is an example of the international community’s efforts to update its understanding of severe exploitation and to develop strategies to combat it.

The Trafficking Protocol, formally known as the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, is the first comprehensive international criminal justice instrument against human trafficking. It aims to protect and assist victims of trafficking in human beings. It directs states to criminalize a range of offences committed by natural or legal persons, such as participation in an organized criminal group, corruption in the public sector, laundering of the proceeds of crime, and obstruction of justice.

Article 3 of the Protocol outlines three interrelated elements of trafficking. The first is an action: the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring, or receipt of persons. The second is a means: the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability, or the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consented-to control of one person over another. The third is a purpose: exploitation. Although it does not attempt to define the term, the Trafficking Protocol clearly states that it should include, at a minimum, the exploitation of prostitution, other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude, or the removal of organs.

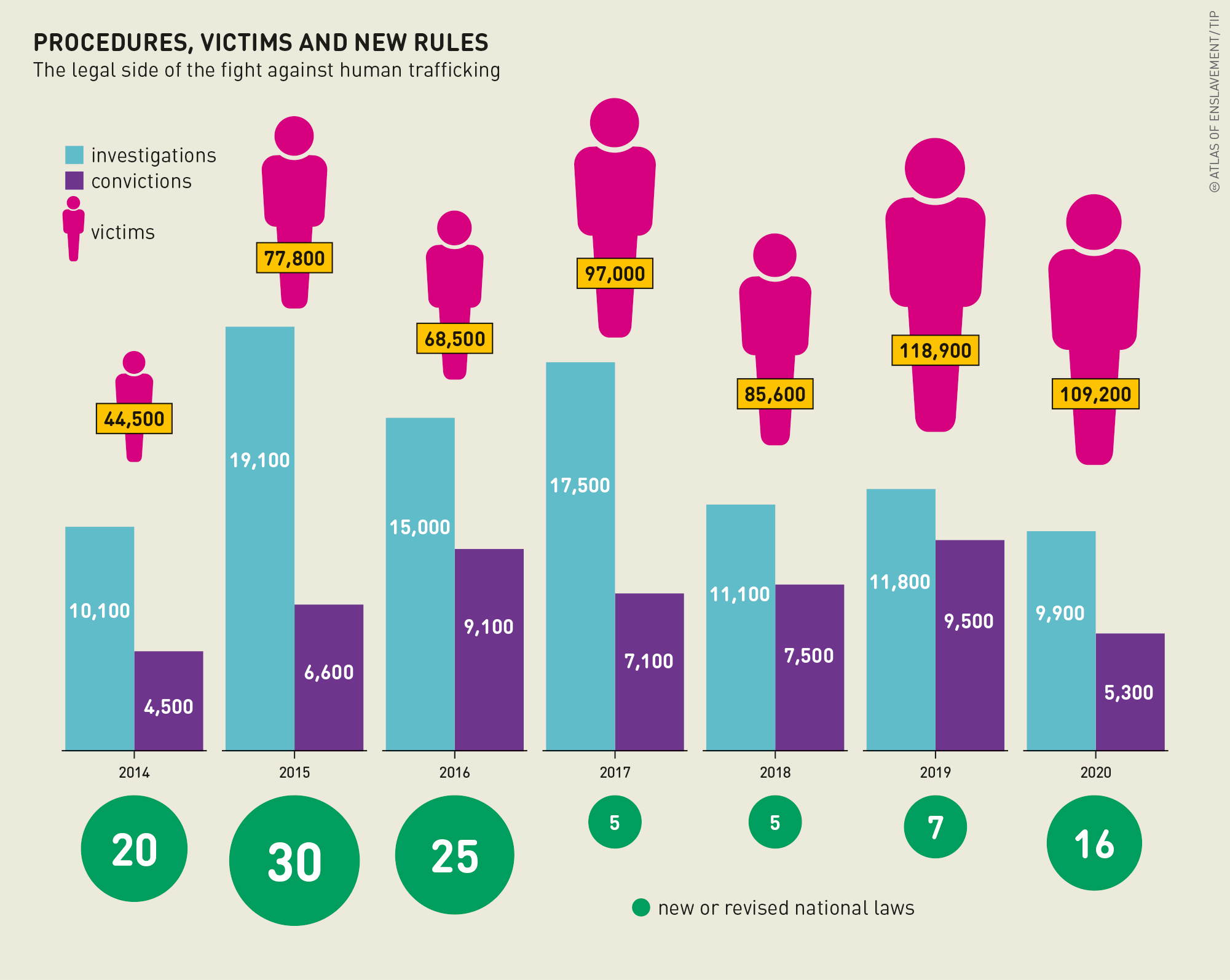

The Trafficking Protocol is one of the most widely ratified UN instruments. Since its adoption in 2000, almost every State Party has developed new anti-trafficking laws or amended old laws in accordance with it. As a crimefighting tool, it is weak in terms of human rights obligations towards the victims of trafficking. However, the Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking, issued by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in 2002, fill this gap and provide comprehensive guidance in this regard. Regional anti-trafficking instruments in Europe and the ASEAN region, which are in synergy with the Trafficking Protocol, also have strong victim protection mechanisms.

In the first few years after the adoption of the UN Convention, the focus was on the trafficking of women and children for the purpose of sexual exploitation. This slowly changed, and states began to focus on labour trafficking. In 2014, this prompted the International Labour Organization to update Convention 29 on Forced Labour of 1930, and issue a set of supplementary recommendations on how the updated Convention should be implemented. These two instruments build on the Trafficking Protocol but have clear measures to support victims, including compensation.

As the Trafficking Protocol does not have a built-in monitoring mechanism, the Conference of Parties to UNTOC adopted a Mechanism for the Review of the Implementation of UNTOC in 2020. This is a peer-review process designed to assist States Parties in the effective implementation of instruments and to help them identify and justify specific technical assistance needs. With regard to the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, the Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, known as GRETA, is responsible for monitoring implementation.

The world today lacks neither dedicated policies nor initiatives to combat modern slavery. But two decades of intensive engagement have made it clear that dedicated policies, even if well implemented, will not be able to solve the problem. The reality in the world of work today contradicts the basic assumption that forced labour, human trafficking and modern slavery are outliers and can therefore be eradicated through criminal justice measures.

Instead, exploitative practices are embedded in today’s economic paradigm of growth and development, which places profit above people. An international instrument against exploitation is not enough. To address exploitation, it is necessary to address the policies that create or exacerbate vulnerabilities for large numbers of people. Time and energy must be invested in large-scale mobilization and education of workers, especially those in precarious work. And advocacy is necessary for policies that put people’s rights and welfare at the centre.