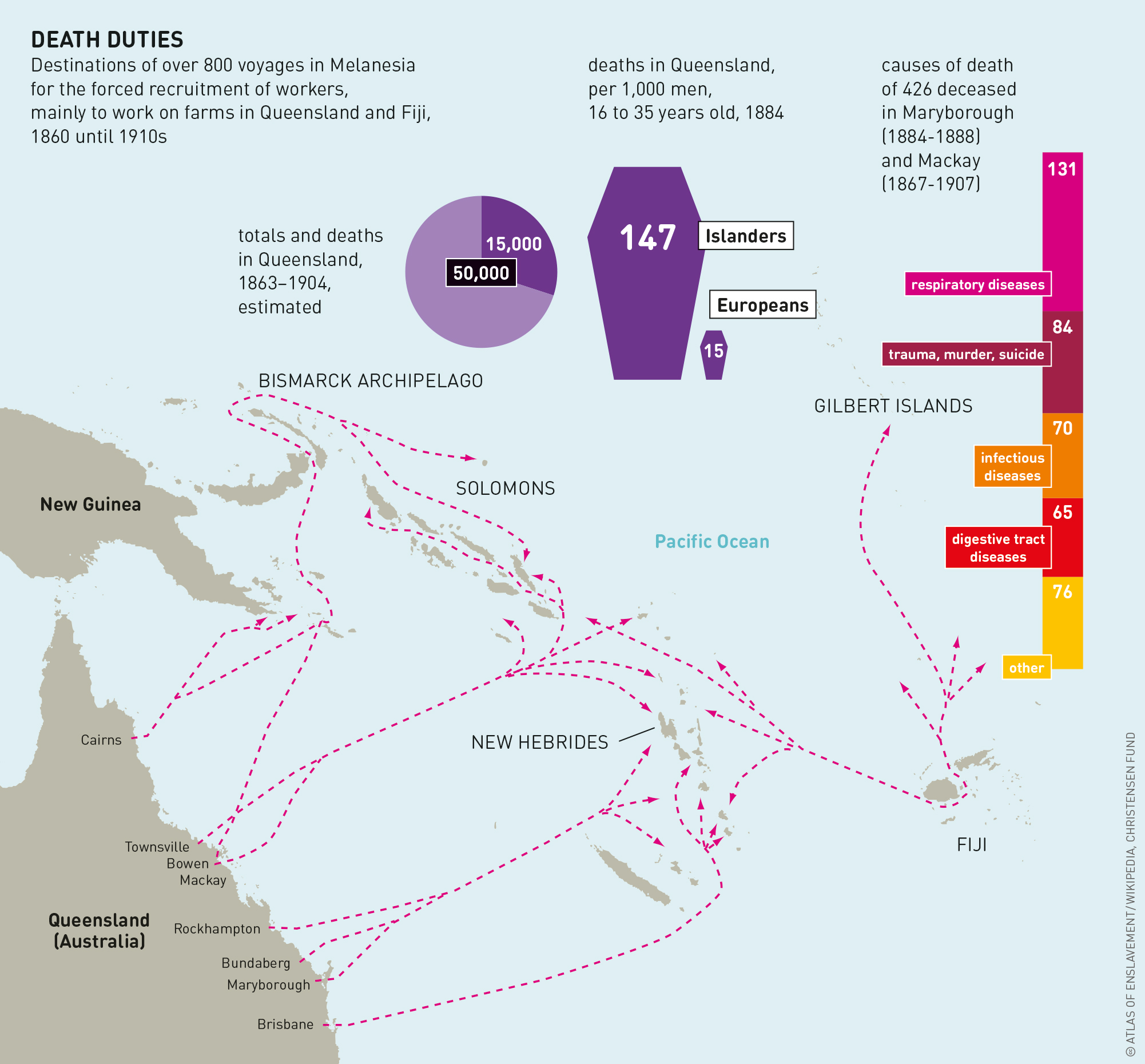

Was Australia home to slavery in the 19th century? Historians disagree on the subject. What is clear: tens of thousands of Pacific Islanders came to work on plantations and livestock farms in

Queensland between 1863 and 1906. Some came willingly, while others, especially early on, were kidnapped or brought to Australia against their will. All endured harsh conditions.

The issue of slavery in Australian history is a contentious one. Historians disagree on whether the practice of transporting Pacific Island labourers into Australia in the latter part of the nineteenth century was a form of slavery. This labour trade is sometimes known as “blackbirding” – a practice whereby Pacific islanders were kidnapped and brought to Australia for agricultural and pastoral work. Historians’ debates focus on the recruitment of the large majority of labourers, on their treatment when they arrived, and whether this constituted slavery or indentured labour.

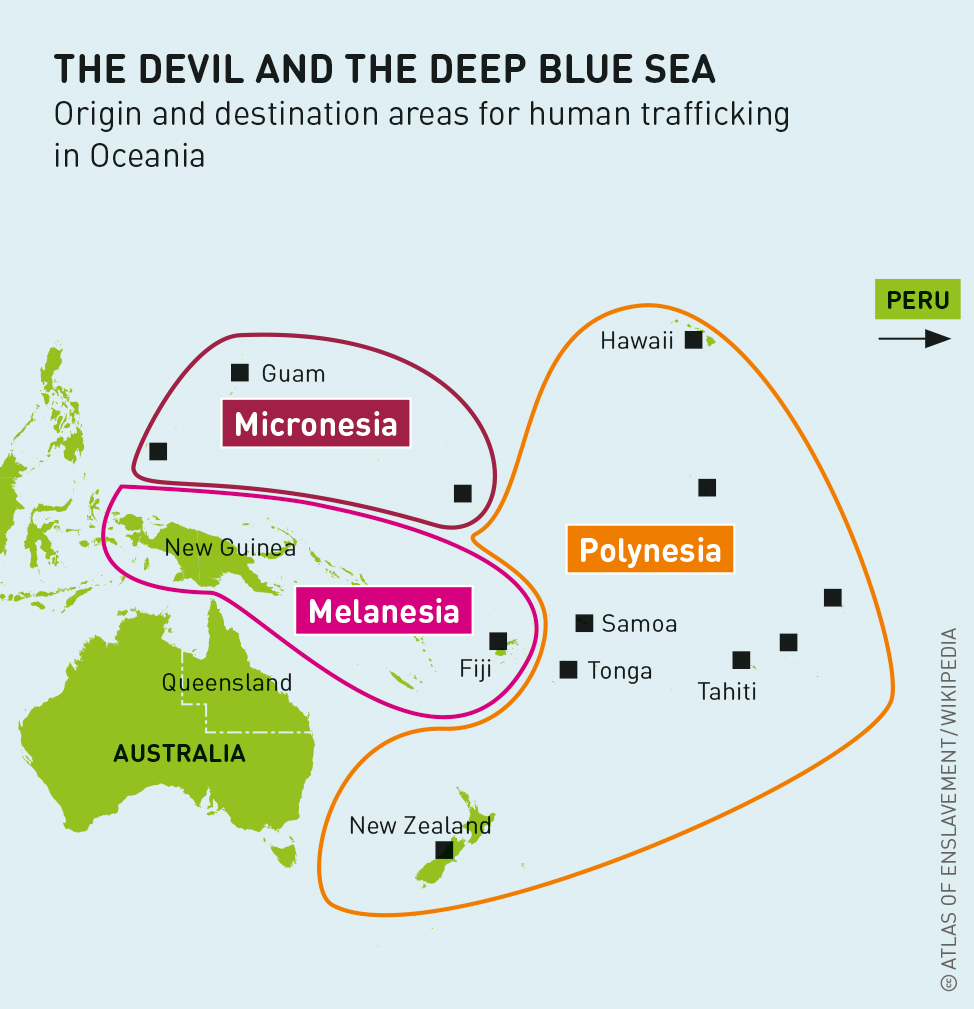

The Pacific Island labour trade involved the transportation of Pacific Islanders by European settlers for agricultural and pastoral work in Queensland, Fiji, New Caledonia, the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), German New Guinea, Samoa and Hawaii. By far the biggest destination was the Australian colony of Queensland. This trade operated from 1863 until 1906 and imported an estimated 62,475 Pacific Islanders into Australia. This figure is based on labour contracts, so the actual number of individual recruits would have been less as many returned more than once.

In the early days, some ship captains took advantage of the Pacific Islanders, resulting in highly-publicized scandals. In 1867, for example, a Brisbane-based ship kidnapped 282 labourers in the New Hebrides and the Loyalty Islands, using intimidation and violence such as burning local islanders’ houses and crops.

Missionaries complained about the kidnappings and made accusations of a slave trade being conducted in the Pacific. This led to uproar in Britain and the Australian colonies. Britain applied pressure on the Queensland government to regulate the labour trade. In 1870, ships were legally required to have government agents on board. Further complaints resulted in strengthening the regulations these agents had to follow, such as informing recruits about the conditions of their service. In 1872, the British Parliament passed the Pacific Islanders Protection Act, which introduced the licensing of labour trade ships and extended British legal jurisdiction over the Pacific Islands.

After the British annexation of Fiji, a second Pacific Islanders Protection Act of 1875 gave Queen Victoria the same power over her subjects in non-annexed islands. This reduced the number of kidnappings. The islanders became better acquainted with the trade and acquired firearms, making them better able to negotiate their labour terms rather than having to succumb to force.

These changes led some historians to revise the traditional interpretation that the Queensland labour trade involved a continuous period of kidnappings. There is little dispute that kidnapping was common in the early years. But this changed later with the new laws and the islanders’ experience with the traders. Indeed, many islanders had a long history of experience with Europeans, going back to the start of the sandalwood trade in the 1830s. They had reasons for offering their services, such as the money they earned. But kidnappings continued. Queensland ships were involved in another kidnapping scandal in 1883–84 when the islands off eastern New Guinea were opened for recruiting.

Research suggests that a large majority of islanders in the Queensland labour trade may not have been coerced into service against their will, or at least against the will of their communities, But there is also debate about their treatment once they arrived in Australia. Different accounts reflect different time periods. Conditions were harsh in the early years of plantation work in the 1870s and 1880s, but they improved over time. They were reportedly better for workers in Queensland than for those on the German plantations in Samoa or in the French nickel mines of New Caledonia, or for indentured Indian labourers in Fiji. But the wage paid to islanders of £6 per year was well below that paid to white workers, and the islanders were tied to their employers for a period of three years. The death rate among the islanders in 1879–1886 was 82 per 1,000. This fell to 35 per 1,000 in the period 1893–1906.

The labour trade ended when the six Australian colonies – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania – united to establish the Commonwealth of Australia. In 1901 the new Commonwealth Parliament introduced the Immigration Restriction Act, which began what became known as the White Australia Policy. A related law was the Pacific Island Labourers Act, which banned the import of island labour from 1904. Except for a few thousand longer-term residents, all Pacific Islanders in Australia were deported in 1906.