On land, it is hard enough for even the most diligent, well-organized authorities to fight modern slavery. It is that much harder when the forced labour happens out at sea – far from inspections and in international waters.

Modern slavery in the commercial fishing sector takes the form of forced labour and debt bondage. These sit at the extreme end of the spectrum of labour exploitation. While the scale of modern slavery at sea is difficult to quantify due to its hidden nature, evidence suggests that it is pervasive. The expansion of the industry to meet the growing global demand for seafood, combined with a general lack of regulation, has led to overfishing and the depletion of fish stocks. The need to earn profits despite the higher costs associated with fishing at greater distances increases the risk of exploitation. Forced labour, debt bondage and other forms of exploitation are used to cut the labour costs that comprise up to half of total vessel expenses.

In 2015, a series of exposés on the exploitation of migrant workers aboard Thai fishing vessels brought modern slavery in the sector to the fore. Subsequently, the European Commission threatened trade sanctions against the Thai government, and international scrutiny intensified. But modern slavery is not confined to one country or region’s fisheries, and national fleets are not uniformly at risk. Most high-risk fisheries are in Asia, home to more than two-thirds of the world’s fishing fleets and 85 percent of all workers employed in the global fishing industry.

Many of the migrant workers who report exploitation aboard fishing vessels are from Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Myanmar. They describe excessive working hours, unsafe practices and squalid living conditions. They also report the neglect of health conditions, starvation and restriction of water, psychological, physical and sexual abuse, and physical confinement. Some have witnessed murder and crew members being thrown overboard. Vessel operators use threats, deception, violence and the withholding of pay and identity documents to maintain constant control over the workers. They confiscate the workers’ documents and control their wages, so that even when the boats are docked, the workers risk deportation or destitution if they escape.

The fishing sector employs large numbers of migrants, who are particularly vulnerable to debt bondage because they have to repay “debts” accrued during their recruitment. While many willingly accept work aboard fishing vessels, some are deceived with promises of better pay. Excessive sums may be deducted from their wages to cover transport, daily living costs and emergency expenses, leaving them with little real income.

In many jurisdictions including Brunei, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, India, Lithuania, Norway, Singapore and Taiwan, national labour laws do not extend to migrants in the fishing industry, leaving them without legal protections. In Thailand, for example, migrant workers are legally barred from forming their own unions – though strong trade union representation is linked to lower levels of forced labour. Many migrants are undocumented, so cannot benefit from labour laws where they do exist. Many do not understand their rights due to language barriers. They may not report on or identify their abusers, and they may be reluctant to escape because they fear being deported or prosecuted.

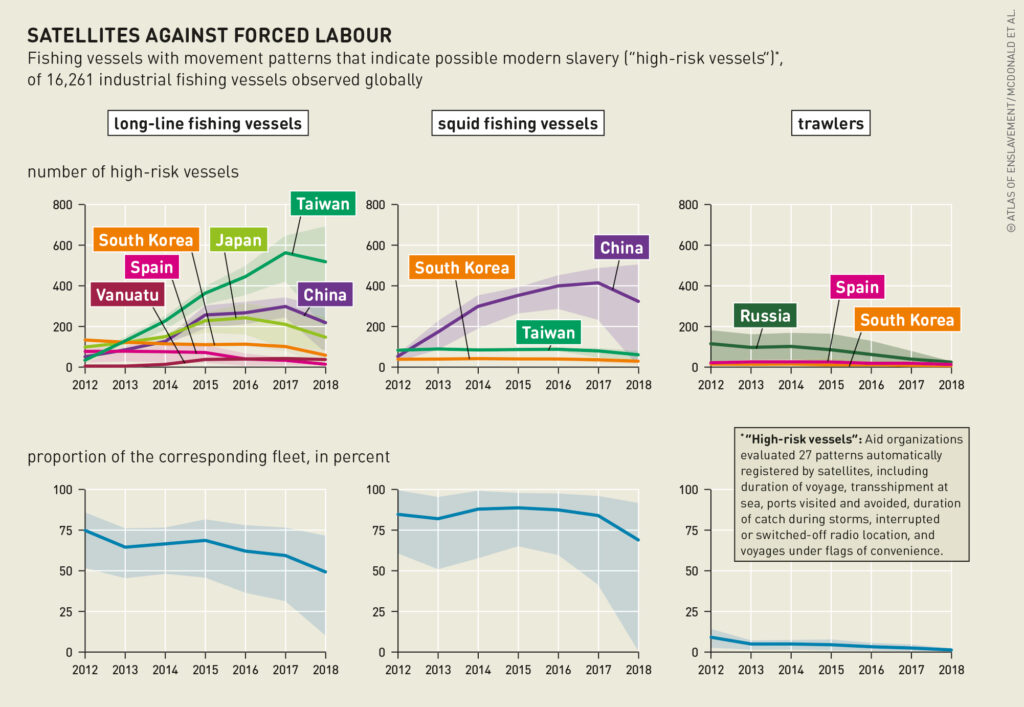

Modern slavery touches many economic sectors. But fishing is especially difficult due to the remote nature of the work, which makes oversight and enforcement costly and logistically difficult. The lack of adequate fishery management is compounded by the need for coordination among several governments and authorities – the coastal state, vessel registration state, port state, and the migrant workers’ countries of origin. Oversight is further reduced for those aboard vessels on the high seas and outside any national jurisdiction. Restrictions imposed to stem the spread of Covid-19 have further reduced protections for workers and increased the risk of exploitation. For example, vessels may not be permitted to dock; workers may not be allowed to leave a docked vessel, they may not be able to return home, and there may be fewer labour inspections.

Modern slavery aboard vessels is often masked by the practice of transhipment. This involves transferring the catch, crew and supplies between vessels at sea; it is done to reduce the need for fishing vessels to visit port. This also enables vessels to evade inspection and allows the prolonged isolation of workers, who may remain at sea for months or even years on end.

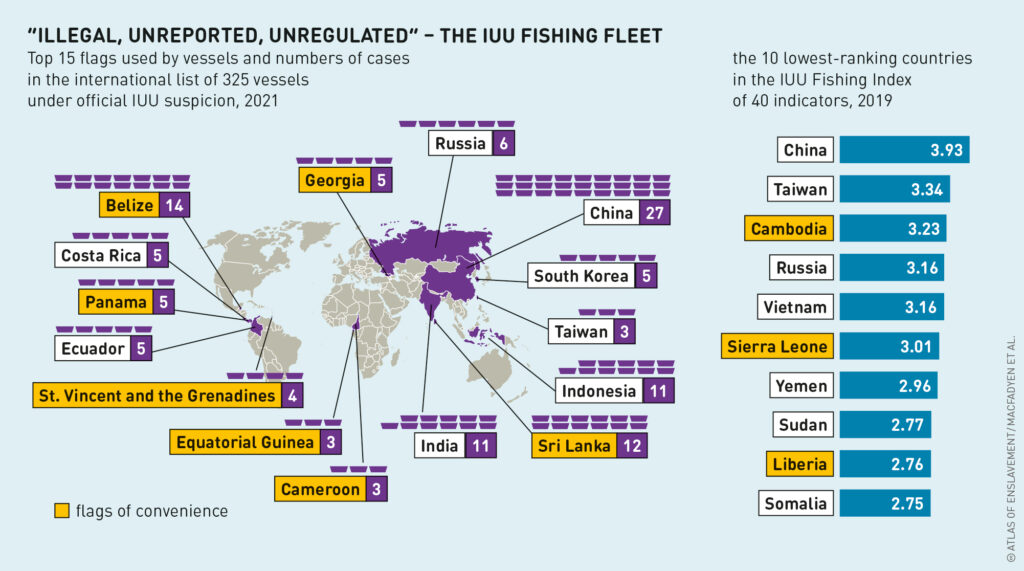

Flags of convenience are another problem. All vessels must be registered under a “flag state”, which is responsible for enforcing international law and working standards on registered vessels. But using a flag of convenience allows operators to bypass labour regulations by registering vessels under the flag of a foreign nation with lax rules. As awareness of the risks posed by these practices grows and fishing nations face growing international pressure to protect the safety of workers in the industry, some governments have taken action to ban or regulate transhipment and flags of convenience.