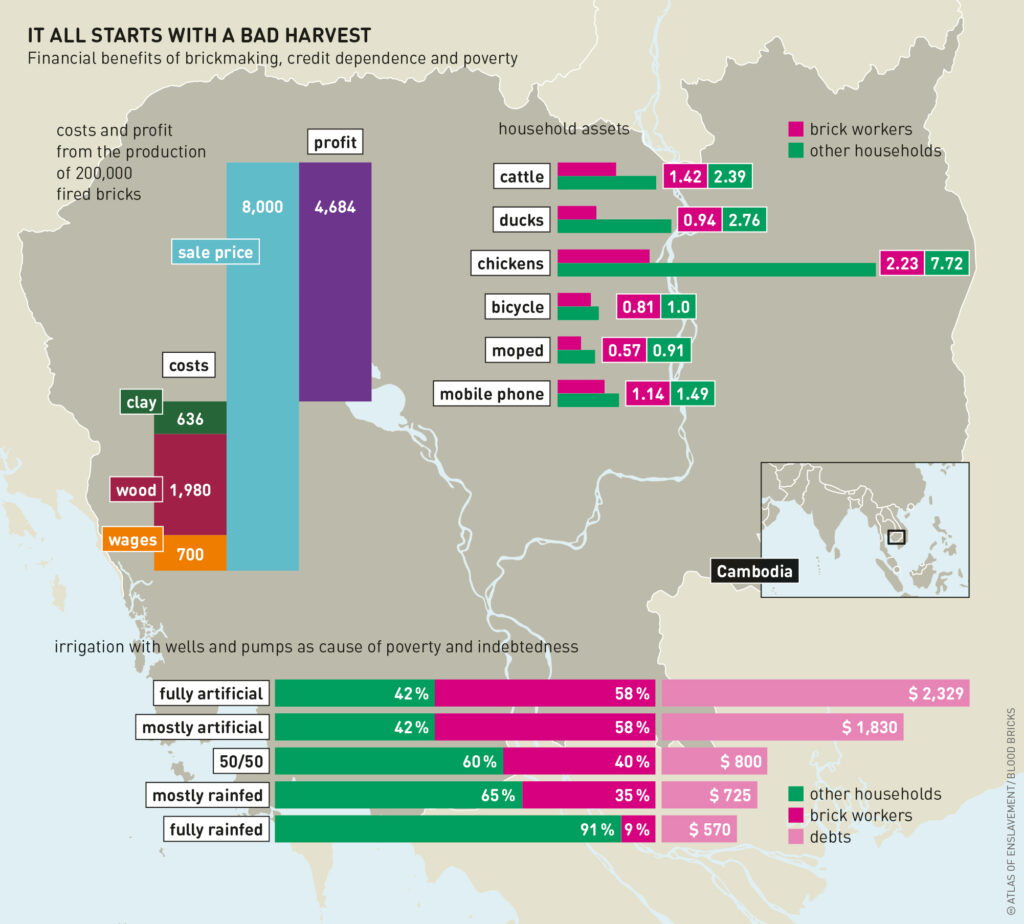

It is all too easy for farmers to fall into a cycle of debt from which they have little hope of escape. One bad harvest, and they must give up their land and seek work elsewhere. Without education or formal skills, unscrupulous employers take advantage.

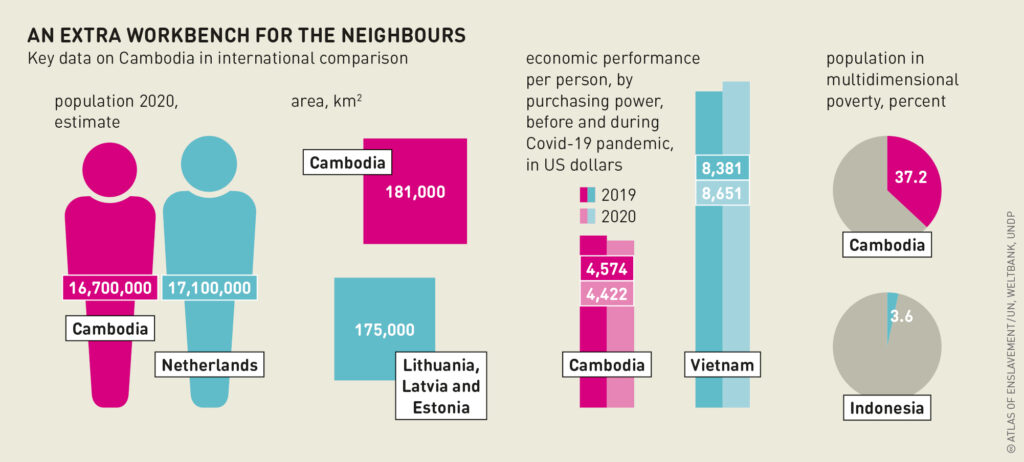

Debt bondage, the most common form of modern slavery globally, is prevalent in brickworks across Asia. In Cambodia, some 10,000 men, women and children work in 450 brick kilns that feed the country’s construction boom.

Construction, funded both locally and by foreigners, has been at the core of Cambodia’s economic success over the past two decades, and the construction industry is now the second most important growth driver in the country, after the garment sector. While modern slavery has been highly publicized in construction for major sporting events from Qatar to Brazil, labour exploitation is a much broader problem. It is integral to significant portions of the construction industry worldwide.

Like most industrial workers in Cambodia, brick workers are mainly internal migrants. They begin their journey to the kiln as farmers and labourers from across rural Cambodia. They fall into debt after borrowing from microfinance schemes to deal with flooding, drought or illness. Lenders charge high interest rates and demand payment regardless of whether a harvest has failed. Unable to service their loans, borrowers have little choice but to accept a loan from a brick factory.

In this way, whole families are forced to move to brickworks and to toil for very low wages to repay their debt to the brickworks owner, over years and even generations. Children as young as 12 have to make bricks. The workers are commonly prevented from leaving, and are arrested and brought back if they try to escape. Such debt bondage is a violation of national laws and international human rights treaties to which Cambodia is a signatory.

At the brickworks, adults and children use hoes to break up large clumps of wet clay, and clean it by removing dirt and stones with their hands. The clay is then carried and fed by hand into automated moulding machines – though the level of mechanization varies from one brickworks to another. The workers push the wet clay into a rotating metal mould. They then carry the wet, moulded bricks out and stack them to dry. The bricks are loaded into the kilns, and after firing, they are carried out of the kiln to cool. Workers use wheelbarrows to take the bricks to the buyers’ trucks, which transport them to building sites in Phnom Penh.

Many of the kilns are fuelled by wood brought from northern Cambodia. Some of this wood is the product of illegal logging, and the workers must unload it at night to evade detection. The kilns also burn garment waste sourced from Cambodia’s main export industry, which supplies European fast-fashion retailers. The workers stoking the fires are not provided with masks; they use cloths to protect their mouths and eyes. But the cloths, like the waste that is burned, often contain toxic chemicals such as bleach, formaldehyde and ammonia. Heavy metals, PVC and resins are also commonly involved in textile dyeing and printing. Burning this material, often for several weeks at a time, harms the respiratory health of the workers who live on site. The workers suffer injuries and long-term health problems from labouring in these conditions and from living in shacks made of corrugated metal just metres from the kilns. Unsafe machinery, extreme temperatures, brick dust, toxic smoke, and overwork contribute to their ill health.

Despite their low wages and poor treatment, some brick workers are able to make money during the dry season. Yet the rainy season brings a different set of conditions. Brickworks are typically unroofed, and workers have to cover the unbaked bricks to keep them dry. Rain can stop production altogether. Forbidden from leaving the kiln site to earn money elsewhere, the workers sometimes need to again borrow from the kiln owner to cover their daily expenses.

The brickmakers have little choice to work in the brickworks. They have no other way to earn money, given the unemployment and poverty in their rural areas of origin. Of the many jobs that these migrants do both in Cambodia and abroad, brickmaking is seen as one of the least desirable. It is an industry renowned for low pay, the indebtedness of the workforce, and its dangerous and difficult working conditions.